Of Ballast and Land Reclamation

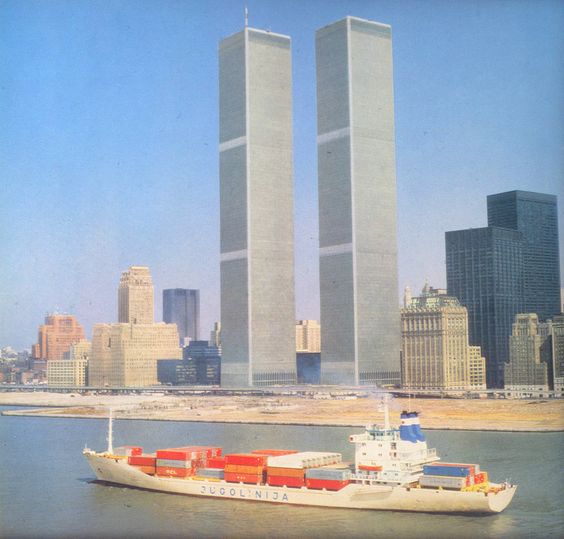

That extraordinary image is from some time in the 1970s, and the container-ship steaming so serenely in Hudson River is a Jugolinija ship belonging to the Yugoslav national shipping line. What is of course poignant about the image is that neither the shipping line nor the World Trade Center towers exist any longer. I think the photograph is staged, as I don’t really think that there were any container ports up the Hudson River at that stage (the Chelsea Piers catered to passenger ships). I first saw this image last weekend in Rijeka (the home port of Jugolinija) in a performance by artists/activists of the art project, Said to Contain.

But what i want to reflect on is the middle ground of the photograph – between the ship and the towers. That 1970s empty space is today Battery Park City, a dense residential and business area. And it was built by reclaiming land from Hudson River by dumping the rubble dug up from the foundation excavations of the World Trade Centre.

Land reclamation is of great interest to me because of my interest in ports, and seems to be of increasing interest the world over. For example, here is a link to an article about Singapore’s land reclamation projects:

Once I began looking for reclaimed land, I encountered it everywhere. The five towers of the Marina Bay Financial Center are built on reclaimed land; so is an assortment of parks, wharves and a coastal highway. Beach Road, in the island’s belly, at one time had a self-evident name; now it reads like a wry joke, given how much new land separates it from the ocean. Most of Singapore’s Changi Airport sits on earth where there was once only water. The artist Charles Lim Yi Yong grew up in a kampong, or village, near where work on the airport began in 1975, so his house looked out onto reclaimed land. “It was a wooded area, but if you walked there, the ground would be sand and not soil,” Lim said. “Then you went through this desert space. It felt like I was in ‘The Little Prince.’ ”

Before he turned to art, Lim, now 43, sailed in the 1996 Olympics on the Singapore team. He grew interested in the sea because he sailed, and he sailed because he came from a kampong on the coast. The kampong has long since disappeared, and the coast has changed beyond recognition. Lim’s major creation, “Sea State,” is an anthology of artifacts and installations: videos and charts, buoys and other nautical paraphernalia. Shown at the Venice Biennale two years ago, “Sea State” embodies Lim’s obsession with his country’s transactional relationship with the ocean. His art is a form of urban exploration, roving over, into and around Singapore, studying what few others see: outlying islets, sewage tunnels, buoys, lighthouses, sand barges.

But going back to New York City, a Facebook friend turned me on to this article which lists a few other places in New York City which are built on the rubble of excavations, but also wars. The one site that really interested me is FDR Drive which seems to be built on the war rubble of Bristol and other British cities bombed during the World War Two Blitzkrieg. Apparently the rubble of those cities was heaved onto ships as ballast and dumped in New York. The above article links to another article in which Michael Ballaban writes

With nearly 85,000 buildings destroyed, Bristol had lots and lots of rubble. Just plenty of it. And when push came to ballast, the Brits just sort of said “screw it,” I imagine, and heaved the remnants of their homes and their factories and their beautiful churches into the bowels of chugging cargo ships.

They dropped so much rubble there, in fact, that the area near the water’s edge between 23rd street and 34th street came to be known as the “Bristol Basin.”

So, cities become rubble become ballast become waste become foundations for infrastructure.

There is also a(nother) colonial story about ballast. I often tell the story of this stone in my talks:

Among the holdings of the British Museum, warehoused in their massive storage among around eight million objects, is a carved dark gravestone inscribed in Hebrew and dated 1333 AD, from the port of Aden in Yemen. The inscription says, “Mayest thou rest in peace until the [redeemer] cometh! (2-6) In the month of Tebeth, in the year 1644 [Seleucid], was gathered in peace to her fathers the worthy, respected woman Madmiyah, the daughter of Se’adyah the son of Abraham (may his memory be blessed)”. The stone was donated to the museum in 1886 by Thomas Holdsworth Newman of the shipping firm Messrs Newman, Hunt & Co. The stone had been brought over to Britain, however, some 30 years earlier, when it had been used as ballast for a ship sailing from India to Zanzibar and onwards to Britain (I have tried to find what sort of ship this was, but have not yet been successful). The shipping firm itself owned whalers in Newfoundland, owned vineyards in Oporto in Portugal, and traded with Mediterranean ports.

There is much about this object that I would love to note here. It speaks of a long history of Jewish diasporic existence in Aden, in Yemen. It bespeaks of an imperial carelessness that plunders gravestones for ballast. And it points to Aden as a significant, perhaps the most significant, coaling station between Europe and India. I want to say a few words about ballasts, and then I shall shift to Aden itself.

In his beautiful short reflection on ships’ ballast, Charlie Hailey recalls Joseph Conrad’s obsession with ballast, telling us that ships are either “in cargo” or “in ballast”, where the weight, here of stone, later of coal and still later of seawater, is required to balance the ship when the ship is low on cargo. Landscapes were harvested of ballast, looted clean of sand and shingle and rock. And although ballast may speak of empty ships, of ships that have delivered their goods in one direction and are now sailing in the opposite direction with their cargo heaved to port, it also speaks of resource extraction in ways that would be considered “unproductive” but which are fundamental to capitalist trade. This resource extraction transformed landscapes in ways that have been forgotten. Once a ship arrived in port, ballast had to be discarded and despite laws that prevented the discharging of stone and shingle and sand into the sea, Hailey tells us that “discarded ballast spawned landscapes born of displaced materials from far-flung lands” and ballast islands and hills, this wastage “became infrastructure, with these unwitting spoils of trade repurposed for buildings, roads, and railways.” Today, when seawater from one geography is released in port in another geography, there is much concern about invasive species, about this uncanny mixing of waters, organisms, pollutions.

And the harvesting and dumping of ballast also echoes through the dredging and land reclamation processes that transform landscapes, looting far riverbeds of Myanmar for example for gravel to be poured on the seabeds of Singapore, or of ancient marine topographies ripped up to accommodate ships with deeper draughts. This is crucially important. The making of ports and transport infrastructure in one place requires the despoliation of another place. A port in Singapore or Dubai requires the ecological devastation of another country’s riverbeds.