Shooting the animals

This post does not strictly have to do with shipping but it is fascinating and it has taken me on a tangent (and I love these tangents that end up weaving the world together). I am reading the memoirs of Violet Dickson, whose husband Harold Dickson (formerly Political Agent in Bahrain, latterly the Political Agent in Kuwait) served in Bushehr as Political Resident between 1928 and 1929.

Her account of the time in Bushehr is brief, but there is this short and oblique reference to the devastation left in British wake:

Bushire is almost an island, being completely cut off at high tide except for a causeway across to the mainland. This causeway was known as the mashaila, and on the edge of this salty muddy stretch we came across the bones and dry carcases of hundreds of animals -mules, horses, and cattle, which, we learnt later, had been shot by our troops when leaving the country after the First World War. (p. 68).

In an earlier post, I had written about the Tangsiri revolt against the British. What I hadn’t mentioned in that earlier post -and which I did not know- was that the Tangsiri grievances antedated the First World War, and according to this site (which is a cheerleader for British imperial military conquest), the Royal Navy “had destroyed many of Dilwar’s fishing and cargo vessels in 1913 during a dispute over piracy.” Piracy, of course, has largely been used by imperial powers as a euphemism to indicate an indigenous group’s refusal to pay taxes or customs or fees to the empire. The same site also helpfully lists the massive force deployed against the ragtag army of Tangsiri rebels:

“On 10 August 1915 a British expedition left Bushire to carry out punitive measures against Dilwar. The ships involved were:

- “HMS Juno (Captain D St A Wake) – 11 x 6-inch, 8 x 12-pounder and 1 x 3-pounder guns.

- “HMS Pyramus – 8 x 4-inch and 8 x 3-pounder guns.

- “HMIMS Lawrence – 4 x 4-inch and 4 x 6-pounder guns.

- “HMIMS Dalhousie – 6 x 6-pounder guns.

“The designated landing party, under Commander Viscount Kelburn, Royal Navy (HMS Pyramus), consisted of:

- “Captain G Carpenter, Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI), with 50 NCOs and marines and from HMS Juno.

- “9 marines from HMS Pyramus.

- “11 Petty Officers and seamen from HMS Juno manning machine guns.

- “A demolition party of 1 Warrant Officer and 20 men from HMS Juno.

- “4 signallers from HMS Juno.

- “1 Medical Officer and 10 stretcher bearers from HMS Juno.

- “24 Seedie Boys (locally enlisted stokers) acting as ammunition and machine gun carriers.

- “Major C E H Wintle with one officer and 280 sepoys of the 96th Berar Infantry.

- “5 machine guns.”

“Once in the fort the British destroyed it and New Dilwar. Wintle then commanded a fighting withdrawal back through the sepoy company at Old Dilwar and then all the way back to the beach. Naval guns and the machine guns covered this withdrawal which was completed with the loss of only six men wounded. ..The Tangistanis were believed to have lost a considerable number of men.”

When a few months later the Tangsiris attacked the British in Bushehr, they were bloodily repelled and the British used local collaborators, allies and proxies to drive back the rebels. The South Persia Rifles (the British were remarkably unimaginative in naming their proxy militias, cf. King’s African Rifles, e.g.), under the command of Percy Sykes (of the Sykes-Picot fame) were crucial for suppression of the southern revolts from 1915 onwards.

The Tangsir revolt was followed by the Qashqa’i revolt(s), led by Mirza Ismail Khan Qashaqa’i, Sawlat al-Dawla (also transcribed as Soulat al-Doule), Sardar Ashayer. An oral history account of the revolt by Sawlat al-Dawla’s son traces the causes of the revolt, and recounts how their defeat by a combination of Spanish Influenza (then decimating the world), typhoid, and British force.

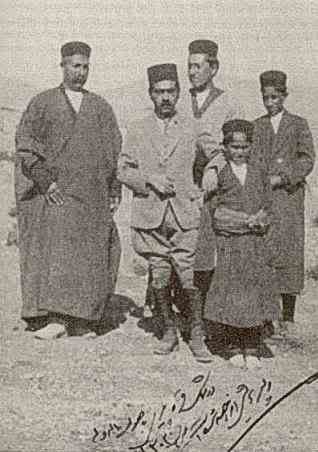

Sawlat al-Dawla (far left) with his sons, who themselves led subsequent revolts against the British and Reza Khan Pahlavi, and later the Revolutionary Guards

While Qashqai factionalism aided this eventual defeat, a regional famine brought on by war and the British expropriation of food and supplies for their forces and British brutality via their proxies, the South Persia Rifles, were also factors in the Qashaqa’is eventual defeat in 1918-1919. As Steven Ward recounts in his book on Iranian military history,

“the South Persia Rifles’ operations became more punitive, directly attacking the tribal strongholds, destroying crops, and seizing livestock to deprive the tribal chiefs of the means to sustain conflict.” (p. 119).

The killings of animals Dickson cryptically recounts must refer to this destruction of the tribes’ logistical apparatuses. Or else, to the British destroying their own supplies as they withdrew from the region, lest they leave anything of value to the troublesome “natives”.