Fouq El-Nakhl: Masaculinities aboard the ship

“and in everything imposingly beautiful, strength has much to do with the magic.” Herman Melville, Moby Dick

The first incident of its kind happened last night. Hopefully, also the last. I was in the wheelroom in the dark, keeping easy company with my favourite ship’s officer and favourite cadet. One of the below-deck officers who had winked at me earlier at lunch when I had smiled at him came up to the wheelroom. I discreetly stayed away so that they can all converse in SerboCroat, and instead went to the charts area behind the curtains to look at our location on the Admiralty charts. The below-deck officer came to the back, and walking past me, his hand brushed my ass. It was one of those groan-inducing moments: “Really? Just fucking really?” I mean, the act is done so casually as to be plausibly deniable, but honestly, are we doing this shit now? So, I swiftly left the charts area, went back to the safety of the dark in the wheelroom-proper, and then shortly thereafter went downstairs. It all came as a bit of a surprise, since the guys have uniformly been brilliant and respectful.

The shipboard masculinities are fascinating to me, although I am sure a more laddish web of interactions aboard has been attenuated by the presence not only of a woman cadet and the captain’s wife, but also by three women passengers, two of them grandmotherly. But still, there are jokey moments about the soft porn images of half-naked women along the edge of the auto magazine, and the half-hearted attempt by the below-deck officer last night and that of one of the crew members on my first day telling me “So you are working out so you can be sexy?”

It is unsurprising that shipboard life would be masculine, even if relieved slightly in our case by women passengers and cadets. Moby Dick seems to be not only about intensely homosocial love between sailors at sea together for years, but its very central obsession seems to be that of Ahab, who is not only “dismasted” but also unmanned by the whale. But these masculinities are obviously not consistent across time, however much the solidarities of life aboard may echo those of Melville’s time.

Last night’s ambiguous bodily contact also gave me an occasion to reflect on the peculiar masculinities and forms of embodiment that exist shipboard, and the differences between how it is performed among the deck officers; the engineers; and the Asian crew members. There was not too long ago a fascinating piece about the making of metrosexuality and spornosexuality in the Northeast of England, and its emergence in the aftermath of the devastation left by Thatcher. The guy who came up with the term had this fascinating thing to say about it:

“It’s fitting,” says Simpson, “that in a post-industrial landscape, the lads in these programmes work on their own bodies in the gym instead of someone else’s property/product down the gym or the shipyard. The ‘structured’ reality is their own hyper-real bodies.”

Simpson goes further, providing a socio-historic explanation for the Geordie attraction to sporno. “The North East was carpet-bombed by Thatcherism in the Eighties,” says Simpson. “Coal and shipbuilding disappeared and were replaced by shopping, service industries, gyms and tanning salons. Metrosexuality and then spornosexuality both took root in the North East because a new generation of young men had to adapt to the wreckage around them, while their fathers’ traditional ideas about masculinity were as redundant now as they were themselves. The post- industrial North East ended up being on the ‘coalface’ of metrosexuality and then spornosexuality.”

In some ways, the muscled (especially around arms) physique of the former Yugoslav deck officers says something about this. It also probably has an element of inducing command and respect (a bit like birds that expand their bodies through puffing their feathers in order to look bigger and more intimidating). Even the woman cadet does body-building (although she follows the new-fangled Crossfit dicta, she mostly seems to do the body-building reps rather than the cardio kinds). Even the lovely ship’s officer who used to be a football player and has the lean elegant body of a football player is now building his arm muscles. Meanwhile, not a single one of the engineers, not even the cadets, builds their bodies, and in fact they all have puny arms and proper bellies. And of course the Asian crew members (and officers) are all lean and wiry and their muscles have the taut strength that comes from work rather than the skin-bursting bulk that weight-lifting creates.

I wonder how typical this spectrum of corporeal self-making is on other ships. I will have to ask the others who have taken freighters.

11.00

Had a chat with the captain today who showed me quite a bit about what they are carrying and the way the cargo is organised (including the yachts they are taking to China whose masts I had seen by the engine casing on the upper deck). He did mention a few things that were fascinating to me. First that this ship –his first 13,000 TEU ship- is far too quiet for him. He liked the accommodations being aft, on top of the engine, in his previous ship, and his body being able to read the vibrations of the engine. He said “even when the engine changed by a few rpms, I could tell.” The quietness of the engine on Corte Real now alarms him, because he says he can’t tell if the ship is running or not. He mentioned how when the wheelroom was on top of the engine, everything vibrated so much that the metal ceiling panels would go “drrrrrrrr” and had to have crumpled paper stuck in the interstices of the metal ceiling panels to stop them from shuddering so much. Some nights, the captain said, the engine vibrated so much you couldn’t sleep, and there was one cabin in particular that had to be left unoccupied because the vibration was particularly intense therein.

And yet, he misses the vibrations. I suppose if you have acquired a skill in your bones, a way of reading objects and material things that has accumulated in your body in subconscious ways, then the discomfort of vibration is compensated by the knowledge it imparts to your muscles and sinews. It is a way of making your body learn: a bit like how the able seamen can perceive disturbances on the surface of the sea with their naked eyes that using binoculars, I could only just distinguish from the regular churning of the billows.

The second thing he mentioned is that he feels that the ships are lot less safe than they were in 1978, when he started as a seafarer. He feels that the dependence on machinery and computers, and the requirement of speed in unloading and loading cargo –which sometimes forces a ship into a berth at a port at zero visibility as he felt had happened in Rotterdam a couple of years back– makes it really difficult to actually manage the ship and amplifies both the danger and the responsibility for the captain.

***

Meanwhile, as we go through the Gulf of Oman, the radio is constantly crackling with the sound of the Iranian Navy asserting its sovereignty every five seconds and with every passing ship.

And I briefly saw a pod of dolphins. They were swimming aft and we were steaming at speed so I didn’t have time to photograph them, but their gleaming sleek body jumping out of the water was glorious, perhaps precisely because of its ephemerality. This is, however, a hazy polluted sea. With the horizons obscured by a humidity that has been painted with the gorgeous orange of air pollution, and beautiful ghastly yellow and green ribbons of waste and effluence stripe the sea, where yesterday, in the Arabian Sea, it was the silvery currents. The ship cuts through this contaminated flow and the backwash –where it was aquamarine yesterday- is a kind of sludge green today.

22.00

Khor Fakkan port

I have spent most of the afternoon in the wheelroom, talking to various officers, but also to the Captain’s wife. She was telling me that the when they married the captain was a seafarer, and just before they had their daughter, the captain decided to quit the sea and work in the port. This obviously made their domestic arrangements much more amenable for all. But then, ten years later, when the Yugoslav War broke out the port of Rijeka was closed, and the city itself became a refuge for others escaping from other parts of Croatia (the woman cadet was mentioning that her family sans her father were refugees for a time in Sweden). At that point, desperate for a livelihood, the Captain (who was not yet a captain) had to go back to sea. They thought this might last a scant few years, but she said, “It has been twenty years now.” The Captain this morning also was speaking longingly of retirement in about eight years’ time.

We are now at port in Khor Fakkan.

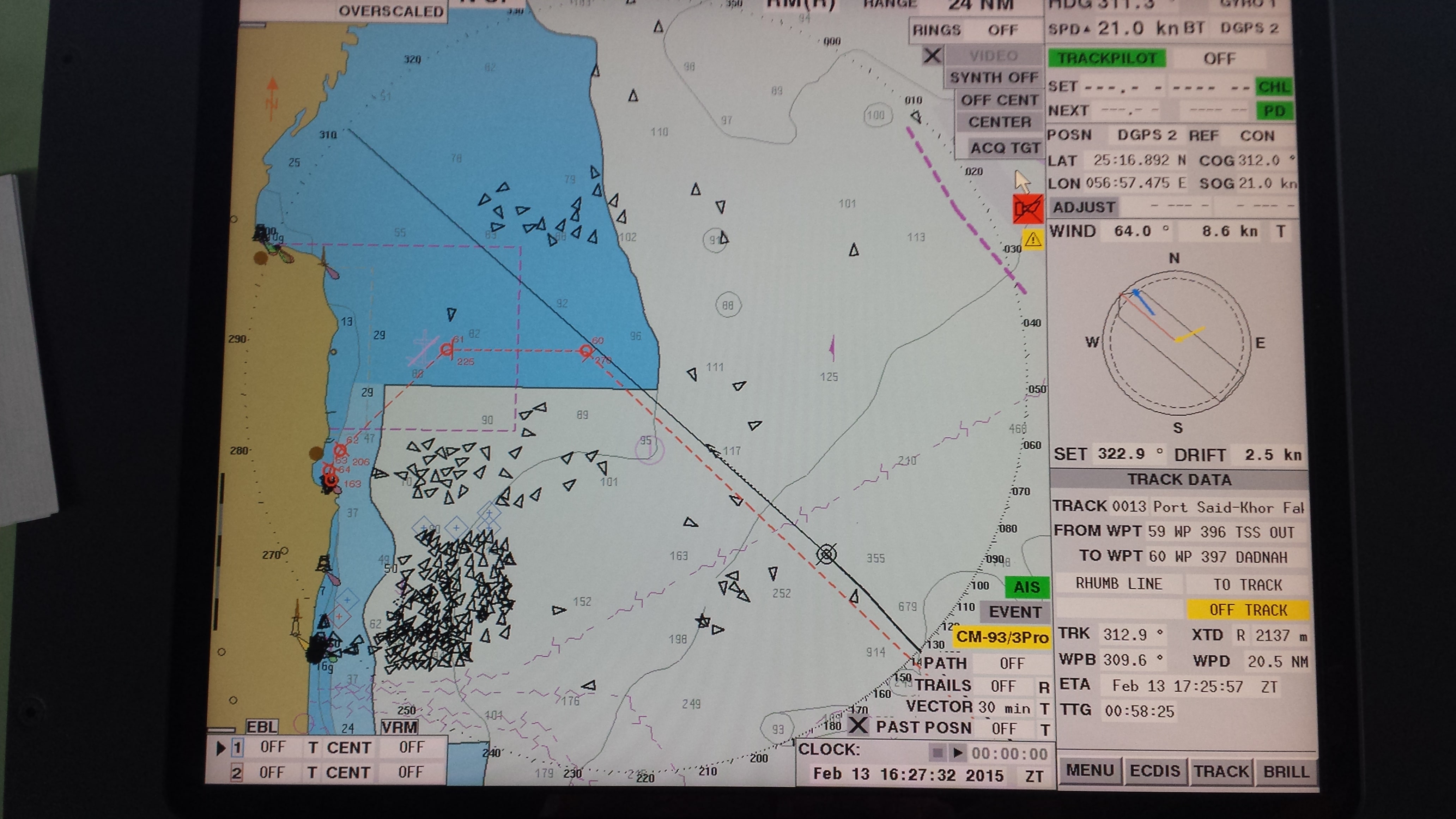

The clump of black triangles in the bottom left corner are tankers and chemical carriers at anchor just outside Fujayrah Port (which is one of the biggest oil terminals in the Middle East).

As we approached Khor Fakkan, most of the afternoon, over the radio I could hear voices and languages and conversations that made me melt with memory. Iranians with bandari accent (saying “chenge de chennell” as if it should be followed by “bachcheh”), some calling to each other in Farsi, some speaking to other boats or ships in English. But mostly strange, momentary, transient conversations between people conducting their day to day routines of work. “Hamid Hamid Hamid, kojayi? Nemibinament!” Or men speaking in a language that was either a form of Urdu partially intelligible to me, or some deliciously mixed littoral dialect of Farsi. The sea was dense with tankers at anchor, and the radar screens showed ridiculous numbers of ships awaiting loading at the Fujairah port just south of Khor Fakkan. The sheer number of tankers –and the varieties of accents of their crews- was astonishing. The Croatian officers were telling me that many of the tanker crews were Indian. Where we had steamed through empty seas next to Yemen, and where we had seen maybe two dozen ships on the AIS next in the northern part of the Arabian Sea, here, there are hundreds of ships –and that is even not mentioning dhows and fishing boats and an occasional “sailing vessel” (as identified by the AIS)- and perhaps the very many anonymous numerous military ships that work the security seas veiled from the AIS.

We had to circle around the anchorage zones for Fujairah in order to come to the Khor Fakkan harbour. Close to the town of Khor Fakkan, and starting just north of it, the mountains that I think stretch to the majestic Musandam Peninsula begin looming jagged behind the lights of the coast.

By 19.00, the pilot had boarded the ship. He was a man of girth and loud exclamations and authority, and I think he may have been Sudanese or Egyptian. It took about an hour and the help of a whole series of beautiful new green and red tugboats with names like Mudaifi and Muhaibi and Al-Khan to push us into our berth at the port. We were there by 20.10; and by 20.20 the cranes were already moving, and the armies of flatbeds were lining up underneath us on landside to move the cargo we (well, the cranes) were offloading. I will have to write down the exact number of containers being offloaded and loaded back on; but the captain seemed to think that our draught will be 80cm shallower than what it was before which means many of the containers we are loading will be empty ones headed for Southeast Asia and China. This shallower draft is also necessary because I am not certain that Jabal Ali can handle a draught of more than 16 metres.

The loading shall go on throughout the night.

The one thing I had not quite anticipated, as I watched the early stages of the port-work- was that beautiful slender young port-workers climb the cranes’ spreaders and fly down to the top of the mesa mountain that are loaded containers on the deck. They jump down with long poles in their hands (being in the midst of Moby Dick I was thinking of harpoons) and walk along the containers, coming to their very edge hundreds of feet off any surface (and what surface!), and using the hook attached to the end of their very long pole to unlock the little nodules that lock the containers together. And meanwhile the enormous crane spreaders bearing filled containers moves back and forth over their head, lifting containers to be unloaded (even empty, these containers weight 3600-3900 kgs). It is the most terrifying spectacle I have yet seen: such literal precarity, walking alongside steel precipices that would give you vertigo even if you had none before, and having enormous containers (superfluously labelled “Super Heavy”) flying overhead, attached by only 4 little corners to a machine that one hopes does not suffer from metal fatigue or frayed cables.