Marsaxlokk-Jabal-Ali: Besotted with the sea

6 February 2015

“For a ship is a bit of terra firma cut off from the main; it is a state in itself; and the captain is its king.” (Melville, White-Jacket – did Conrad plagiarise Melville as I often think he does? See the Conrad quote I use as an epigram)

This might have been one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life. I am besotted with this time-place in ways I never imagined one could love a time-place, given my unapologetically worldly rootlessness. Or maybe I do have an experience of this feeling, but it was always so fleeting, so viewed through the lens of the spectacle that is New York. This besottedness with the shipboard experience is a bit like how I love New York at twilight.

Everyone loves New York a little: It is embedded in our memories, our visual cortex, because we have seen it on screens big and small. We know it before even visiting it. New York at twilight is the spectacular time-place par excellence and I have loved it the way I feel the surge of desire, of ecstasy, in being aboard this enormous ship. The same intense, ephemeral sense of utter happiness. Utter contentedness. The same sense of utter astonishment at being alive and for being here, in this moment made of metal and machinery, swell, sea air, distance and depth and the familiar courtesy and community of shipboard life. The pink twilight of polluted air in New York is like no other urban chronotope (or is it what Foucault calls heterochronies; heterotopias located in time). And the darkness in that quietly humming wheelroom tonight made me feel exhilarated in the same way a New York twilight might. The one lasts as long as twilight lasts – the other you can carry with you all day. And all night. And even as you sleep. Were I to be reincarnated, I would come back to steam the seas.

I have quoted Foucault on the ship as heterotopia elsewhere – but again I want to recall that even Foucault falls for the seductiveness of the sea; and of the ship ploughing a furrow through the sea:

Brothels and colonies are two extreme types of heterotopia, and if we think, after all, that the boat is a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea and that, from port to port, from tack to tack, from brothel to brothel, it goes as far as the colonies in search of the most precious treasures they conceal in their gardens, you will understand why the boat has not only been for our civilization, from the sixteenth century until the present, the great instrument of economic development (I have not been speaking of that today), but has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination. The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.

I have to say here that Casarino has gently challenged the kind of timelessness, ahistoricity, Foucault seems to attribute to ships. In his “Gomorrahs of the Deep”, Casarino writes,

While Foucault’s claim stretches from the sixteenth century onward, I am interested, rather, in the final terminus of the whole process of development of the ship as the heterotopia par excellence. In the nineteenth century the sea narrative, while recording the most glorious historical moment of the ship, was also thoroughly imbued with premonitions of a future—namely, the twentieth century—in which the heterotopia of the ship would be inevitably relegated to the quaint and dusty shelves of cultural marginalia. The nineteenth-century sea narrative freezes the world of the ship into a fleeting image flashing onto the screen of history for one last moment before its disappearance; it captures simultaneously the apogee and the end of the ship as the heterotopia par excellence in Western civilization.

The problem is that Casarino’s entirely persuasive act of historicising ship narratives doesn’t get at that affective specificity, that breathtakingly precise sentimental seascape, that Foucault manages to evoke which feels so much like what I feel right now. Nor does Casarino really get at the experience and practice of shipboard life itself, even as he writes about sea stories. He is writing about literature and his insight applies well to them, but not to the ship, nor ships in history. In fact, Foucault in his sweeping trans-historicism recalls Braudel’s long sweep and points to the massive importance of circulation in the economic history of capitalism in the way that Casarino’s narrower focus –on the sailors’ homosociality; the US Navy, and these works of literature– manages to miss. In a sense, and as always, Allan Sekula gets it right. Although, Sekula says, Foucault’s words betray a kind of “boyish romanticism”, nevertheless,

Foucault’s historical sources for his understanding precede romanticism. Implicitly, Foucault was returning to the image of the late medieval Narrenschiff, or “ship of fools,” analysed in the first chapter of 1961 Histoire de la folie. The shipborne banishment of the madman produced a voyage that “develops, across a half-real, half-imaginary geography, the madman’s liminal position on the horizon of medieval concerns.” [Madness and Civilization, p. 11].

I am afraid I suffer from a bit of “boyish romanticism” here, genderbending notwithstanding.

I spent two hours in the wheelroom after dinner last night. Much of it was spent speaking to the Montenegrin third mate whose four-hour shift ended midway through my visit and the Filipino second mate whose shift began midway through my visit. But some of it was also spent staring through the wide windows at the darkness. And the sea. And the bank of containers stretching out towards the bow. In that velvety moonlit darkness, the world glows luminous charcoal grey – with the sea and containers different textures and the darkness relieved by a limpid moon, two days after its fullness. Melville in White-Jacket manages to capture this too: “still with brooding darkness on the face of the deep. I love an indefinite, infinite background—a vast, heaving, rolling, mysterious rear” (White-Jacket quotes courtesy of Casarino).

The wheelroom is kept entirely dark at night, curtains separating the moderately lit chartroom from the control instruments.. The second mate told me that on nights not lit by the moon, the officers sometimes bump into each other. He laughed easily and sweetly when remembering the dangers of carrying a coffee into the wheelroom in such darkness. But tonight was not pitch-black and that glorious moonlit luminosity – with the rhythm of the sounds of the machinery and the bass-line of the thrumming engine and creaking metal is rather thrilling. The ship is going through the sea at 19 knots at 75 rpm. Apparently, another officer tells me, the previous chief engineer did not like the engine to go above 90 rpm which limited the speed of the boat. One wonders about the demands of these two ends of the ship; the engine room in the aft, in the bowels of the ship; the wheelroom in the fore and atop the whole ship. It reminds me a bit of the way the seating arrangements at dinner reflect these hierarchies. The deck officers sit to the right of the Captain, descending from chief officer down to the third officer (with an empty place always reserved for the Filipino ship’s officer who eats with the Filipino crew); and the engineers sit to his left, from the chief engineer down to the electrician. And the woman cadet on her first sea-journey sits across from the Captain at the bottom of the table.

There is in that wheelroom a sense of the wonder of the sea. I know I am romanticising, but I am also struck by the ease with which the officers with whom I have spoken openly admit the lure and allure of the sea – at least at first when they go to sea without knowing what awaits them (though some know, being the children of seafarers). Even the Filipino ship’s officer, speaks of going to the sea as something distinct from remaining behind or travelling to work on another, a strange, shore. And I suppose between life on the land, with its limited horizons and the inherent conservatism of attachments to a world of everyday pettinesses, I would also opt for a sea that seems so endless, so vast, so deep. I know I am repeating the prejudices of every person who loved a shore, a coast, port-city, but I think I would rather also throw my lot in with Foucault and his outrageous claim for the dreamworld of places that dream of going to sea, this fragment of infinity. Or with Ishmael who goes to sea “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul.” It isn’t just the dreamworlds, it is also the inevitable detachment from land; the worldliness of a ship such as ours that has at least 4 nationalities of people working aboard it, all speaking across their national boundaries in a language (admittedly imperial) not theirs. No authenticity-mongering here, as your ship moves from port to port and brothel to brothel, from language to language and time-zone to time-zone.

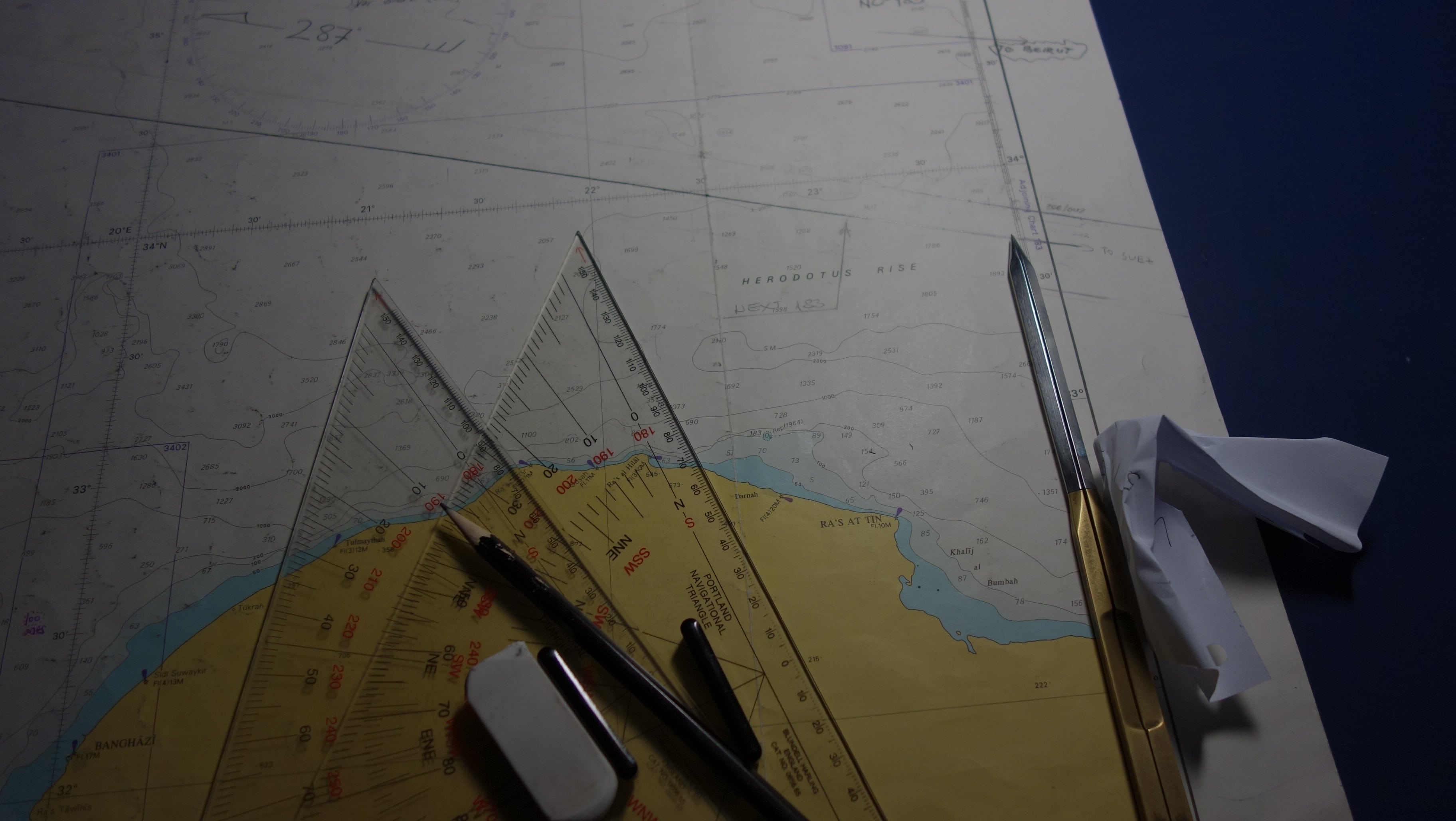

In that wheelroom, another source of dubious wonder is the Admiralty charts. It is strange to see the British Empire’s claim to rule the waves (“first printed in 1823,” they say) embodied there in these drawers full of charts with their exquisite details and still more exquisite names for regions of the sea. I had never thought of a named territoriality of the sea, but there are seamounts and rises, and abyssals and trenches; and they have strange and dreamlike names. And there are ports whose names map worlds, wars, histories (Benghazi, Misurata, Ras Lanuf, as we sail 3 degrees north of Libya). And the Admiralty map is full of admonishments – about explosives dumping ground in the sea just off Misurata; of a firing range just south of Benghazi which “the government of Libya” (which one?) has closed off to marine traffic. The Admiralty maps warn of oil and gas platforms and installations not marked on the map because of their “complexity and constant change.” And it cautions the ship not to draw its anchor across the seabed– because not all pipelines and undersea cables are marked. And it has something about tunny nets as well. So, they are not the romantic sublime of staring at an infinite sea, but a rendering of a sea that is already a place of commerce from its dark depths to its variable surfaces and named eddies, seamounts and watery chasms.

I can spend hours staring at these Admiralty maps, with their beautiful topography of the sea and seashore, and with the pencil-drawn lines with which the deck officers mark our angle of travel and interrupted with our position every hour or two (and the ghosts of the previous routes erased already). And as we inexorably speed off this chart to the next, I await our arrival at the head of Suez Canal.

Afternoon

The captain told me this morning to feel free to go to the upper deck when I so wish – but to be sure to tell the deck officer. And wear my hardhat. So I did. It is a strange world down there. I now know that my two Germanic co-travellers (Heidi the Swiss-German from Basel and Hilde the German from near Dusseldorf) didn’t actually know that you can walk the entire circumference off the ship. All you have to do is to go to the upper deck and there, not far off the surface of the sea is a narrow walkway just under the endless banks of containers. The bow of the ship is serene and so silent in the sunshine, with the surface of the sea so dark blue and so close. The aft tunnelway under the containers has raised ridges and is incredibly noisy with the sound of engine –the feel of the engine- thrumming through. And the ravished sea brushed to aquamarine blue. I met the boson and crew members and cadets down there, and will have to spend some time there everyday to see if I can chat with them at all, since this seems to be the one place I can encounter them. It is where the work goes on – with unrecognisable crew in their helmets, overalls, goggles and various other protective gear, sand the surfaces, paint the rusted bits, clean, tidy, move around amidst the noise. The captain’s wife (who had never left her street or town until the age of 50), goes for walks on this walkway once a day, going around 6 times; with the captain going around 10 times apparently.

I shall return to this walk – lovely in its intimacy with the sea and the crew and the metal flesh of the ship, and the vastness of it all.

Meanwhile, a fragment of a thought/observation: I am not sure what to make of the fact that the reproduction print hanging in our corridor is of Hieronymus Bosch’s vision of heaven, purgatory and hell, with the second taking up the most space in the framed panel. But there are all sorts of strange signs around the ship. Down on the Upper Deck, there is a sign about Da’esh not liking French ships and an admonishment to safety at port. On the same deck, the seafarers are told to be vigilant against Asian Gypsy Moths, and hot water, and HP (high pressure?) blasters, and crushed thumbs. In the wheelroom there is a 2009 notice sent to the authorities of Suez Canal where the Suez Canal pilots are told not to use the accommodation ladders (whatever they are) as elevators. I was expecting something about sexually transmitted diseases and dangerous women (and men) at ports, but I suppose those kinds of indiscretions need to remain discreet.

STORIES

Having now spent time on the bridge last night and all of this morning, I feel like I have developed friendly enough relations with a number of different people of whom I can now ask questions without feeling I am being a damned nuisance.

The woman cadet, tells us that she wasn’t the only woman in her 5 year training programme. This is her first ship; she is from seaside town in Croatia and she is neighbours with the ship’s electrician back home (he is one of the officers with whom I came onboard). Her grandfather was a sailor, but she never knew him; she just wanted to go to the sea and she says that “I don’t care what anyone thinks” about her being a woman. She is funny and warm, and easy-going and thus far is treated with great respect by everyone. She ties her long her hair in a tight bun on top of her head, only letting it down at some dinners. She wears tracksuit trousers and T-shirts and has a big chunky watch on her right wrist. This morning, one of the ship’s officers spent quite a bit of time showing her how to update charts and calculate upcoming positions for the ships’ logs. She was telling me that when she was in the cadet school, the professors had put together the material haphazardly; and all in English; so now when she is looking at a wheelroom document in Croatian, she feels like it is written in “Turkish or something.” The power of the technical languages we learn. She was pleased to hear that Darya in Persian means “the sea”; she was destined to become a seafarer, I suppose. Or she supposes.

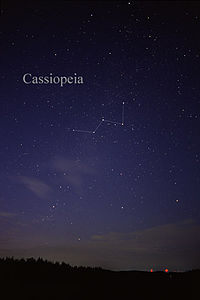

The Filipino second mate told me that he has never been to Iran or to New York for that matter. I was a bit surprised, since he had gone to New Jersey, but maybe the seafarers didn’t realise that it only took a short little train trip to go to the big city. Last night, when I was on the bridge, he showed me Cassiopeia and we looked at the bright planet which the sailors’ almanac told us was Venus (in February, Venus and Mars are evening stars; Jupiter, Saturn and Mercury are morning stars). He was taught about recognising stars and navigation by them at his cadet school and on the bridge of the ships on which he first apprenticed. He has less faith in the durability of the technology than the Europeans seem to have, which may be why he knows more about how to determine where we are in the middle of lonely seas if the machines break down.

He also told me about how different classes of CMA ships have different categories of names (so, for example ships that carry 13,000 TEUs like ours are named after explorers; but there are others named after constellations etc). He also sweetly confessed that he still gets seasick and can’t sleep when the ship rolls so much as it did when coming through the Bay of Biscay when everything had been tied down, hooked, and stowed away. He does indeed eat with the crew and was mentioning that he preferred the Filipino food better in any case. Although we chatted a bit both last night and this morning, I have to speak to him longer. He seems lovely, but also very courteously reserved and I really liked how he was teaching the woman cadet the small things you need to learn aboard your first ship.

The Montenegrin third mate was the officer who initiated me into the conversation with various crew members and officers. He is 26 or 27 and from a small seaside town which has a population of 60,000 people, and he mentioned that he earns $3000 a month where, had he stayed in Montenegro, he would have earned $400. His contract demands that he work 4 months and then take two months break at home. “The time at home goes just like this.” He said he was happy to leave Montenegro behind because ever since he was born the same people have been ruling “and Montenegrins put up with it.” Of “exit, voice, loyalty” he has chosen a kind of temporary exit. But he also mentioned that his father was a seafarer and so the “sea is in our blood.” He is saving for a life-annuity and has an apartment as investment. It was fascinating that in the darkness of the wheelroom, he was not at all shy speaking; telling stories. I will have to spend another two hours there tonight and chat with those on duty… I will try and see if I last long enough to maybe meet another shift of workers…

Meanwhile, a couple of his stories:

I asked him if he had ever been on a ship that had lost containers. He told the story of a ship manufactured in China which he boarded straight from the shipyard. Not far out in the South China Sea, the ship’s engine died. No matter what they tried, they couldn’t get the engine to work. So they dropped anchor. While at anchor, a storm from Philippines blew in, and the ship was hit with massive swells, some up to 8 or 10 meters high. The swells were swaying the ship to such an extent that they lost several containers, which fell inside the hold (rather than in the drink). One happened to be in a non-standard container, as it carried an electricity transformer; when the transformer fell, it descended down an empty column on top of a single container all the way at the bottom, but on its way down it managed to shear off the side of an entire column of 11 containers, damaging them all. Having fallen on top of a container though saved the ship’s ballast tank as that final container absorbed the shock and the weight of the transformer. The Chinese ship manufacturer ended up paying for all the damages. He seems to think that a lot of ship-owners go to the Chinese, because the difference in the cost of a ship between Chinese and Korean ships are $90 million vs $120-140 million. But he (and apparently others) believe that the Chinese ships are not yet as good as Korean ships. Yet.

I asked him which ports he liked best. He said that his favourite was in fact Malta. The port has good weather and is close to the town. The Chinese ports are at such distance from the main cities that it makes it impossible to go the city in the evening. He mentioned a port in China which has joined two islands and transformed them into the port, but the two islands are 50 kilometres by a bridge from the mainland. He thought Hamburg is good, but it is cold so much of the year. He is not particularly fond of one of the big Middle East ports because “their crane operators are crazy.” Apparently, these crane operators seem to operate multiple cranes but all from the same side (starboard at once; or port at once) and it causes the ballast of the ship to be off, making the ship list. What fascinated me was that for him, the liking of a port was a bundle of things having to do with how much it complicated their work life, but also how much easier or difficult they made leisure. The new mode of having ports at some very long distances from the cities is not only one way the dockers and seafarers are cut off from the cities it is also an additional pressure on seafarers who cannot play in the ports in the storied way associated with sailors.

One thing that he mentioned that I hadn’t thought about was that the condition they most suffer on board is not so much tedium as exhaustion, especially when traveling between northern-European ports: Southampton, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Rotterdam, Zeebruggen, and Le Havre – 6 ports in 10 days. He said it is exhausting, and I can imagine it must be if your sleep is short, fitful and disrupted with all the tasks they seem to have to attend to when at port.

I also briefly met the boson, one of the Filipino crew members, and another friendly cadet whose duty is to check the refrigerated containers (or reefers as they are called on the ship). He mentioned that there are 365 of them on this ship and that takes about 1.5-2 hours a time to check, twice a day. When I expressed a bit of awe, he laughed and said, “Well on my previous ship there were 500; and on that ship, there were no walkways to climb to see the monitors; we had to climb the lashing rods.” I said “Good god, and what if you fall down?” He laughed and said, “Well, you fall down.”