More on London canals

I have written lovingly of London’s canals before. I just want to briefly write out something else I have discovered which ties in nicely with the whole infrastructure thing.

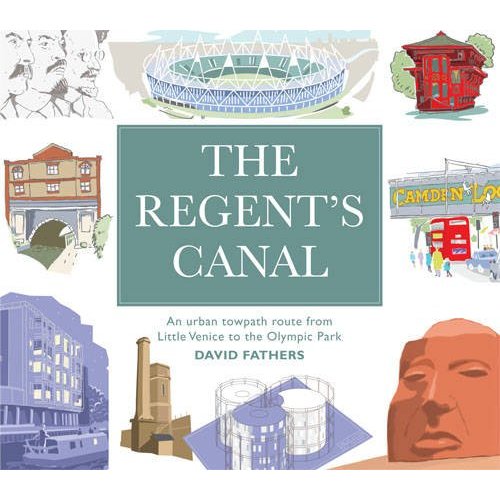

Today I spent an hour or so in the London Canal Museum. Not really a particularly interesting museum. Its location is stunning, and the ice-storage space is the one interesting thing in there (it seems like the two commodities that most frequently travelled on barges on London canals were coal and ice which was shipped in from Norway). I did pick up a little illustrated and annotated route-book about Regent’s Canal, The Regent’s Canal: An urban towpath route from Little Venice to the Olympic Park by David Fathers. The book definitely fuels my running obsession, with its details about what to watch out for in the various segments of the canal. It also has this one very interesting passage:

Following the Second World War and the decline in canal traffic, the towpaths fell into disrepair through lack of use and poor maintenance. These paths were neither intended nor designed for public access.

Between 1968 and 1982 the towpaths were incrementally repaired and opened to the public. Two factors brought this about: action by the local councils through which the canals ran and the needs of the General Electricity Generating Board. The City of Westminster was the first local council to restore the towpath as a thoroughfare for walkers and cyclists. Camden and other councils followed soon after.

The then General Electricity Generating Board needed to run 400kV cables from its substation in St John’s Wood to the East End of London. Normally this would have involved digging up major roads to lay the cables but instead they bought the towpath from Lisson Grove to the Hertford Union Canal, adjacent to Victoria Park. This was a cheaper option; in addition, they could use water from the canal to cool the cables. The flagstones are unfixed for access and can sound like a primitive vibraphone when cycled over.

That explains the development of the towpath in some of the poorer London councils. The book is a pleasure to follow.