Pulp fictions

pulp fiction n. fiction of a style characteristic of pulp magazines; sensational, lurid, or popular fiction.

I sometimes think that pulp fictions touch on the zeitgeist, that they pick up on undercurrents of politics in non-pedagogical sorts of ways -in that they are free from the burden of representation good political-literary fiction is felt needs to bear. In the unpolished presentations of a time, many pulp writers also convey something of the unvarnished prejudices and bigotries of their time without varnishing it.

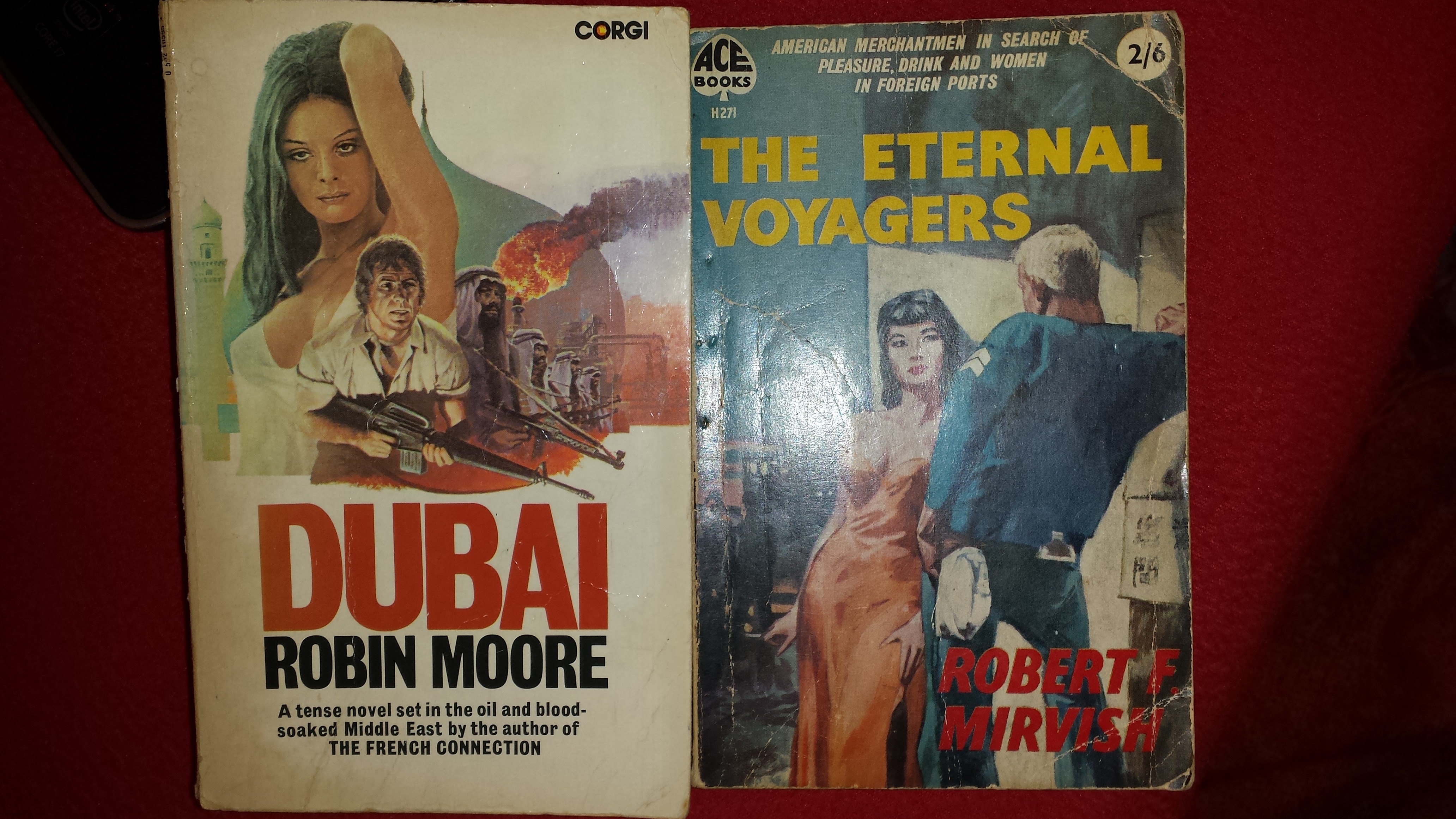

The first of pulp novels here is Robert Mirvish’s The Eternal Voyagers; the second, Robin Moore’s Dubai. The first I discovered when I was searching for something else in the historical NY Times archives and stumbled across a (fairly positive though brief) review. The second was recommended to me by a Facebook friend (thank you Yasser). Neither is at all beautiful in their language, and Moore’s writing is especially atrocious (especially the bad sex scenes. Lord!). Of the two, Voyagers is the better book. Its characters are more believable, their motivations and feelings better described; the story with its own narrative force. But Dubai is more politically interesting, as it touches on events of its time that are little discussed in official histories and stories.

Voyagers is about endless maritime voyages between Kuwait and Japan on a petroleum tanker in the early 1950s. Mirvish was himself a US merchant mariner during and after the Second World War and his sense of the life aboard a ship has a corresponding richness of details and mood. Perhaps the most affecting (because honest?) themes are of the deadliness of the work and of the bruised and strangely fragile masculinities of the sailors. Most shocking though is the unflinching rendering of how crucial alcohol is to the lives of the sailors, how complete its dominion over the ship and the story itself.

Liquor fills a place in the lives of men who go to sea that cannot be underestimated. It has a purpose as important to most merchant seamen as food and rest and recreation. To some it becomes all three, to others it is one or another. It is their consolation in their loneliness, a loneliness so acute and specialized that it is unknown among people living ashore if you dismiss the seaman’s counterpart, the men who fill jobs in the isolated commercial and industrial outposts of the world. It is a companion to merchant seamen in a sense that not every Navy man may know, for a Navy man may be stationed for long stretches of time at shore installations. (p. 38)

For the seamen of the SS Pan Nebraska, thirty days sobriety, of monotony, of work had to be obliterated before they could function as individuals again, with individual desires and tastes. And the tools of obliteration were at hand at last. The beer was ordered so rapidly, each man throwing out his money so eagerly and quickly, that before long the table was covered with bottles, some men having three or four of them open in front of them at one time. As the hours wore away, as the room filled with men from other ships in port, as here and there someone recognized a shipmate out of the past, as more and more people were drawn into the orbit of the big celebration, the first signs of group disintegration appeared. Men wandered off to talk to old friends, to gather bits of information. Questions were asked. Where could one get a woman? What was the prevailing price? What was the procedure? They all knew the answers, but they knew, too, that every country had its own idiosyncrasies.

Strangers drifted together -men from Panamanian ships and Norwegian ships and American ships. Vows of eternal friendship were taken at that stage of the party that by nightfall would be broken by blows. (p.116).

The book’s passages on the work that needs to be done aboard a ship (and what can and cannot be done when the ship has its dangerous cargo of combustible fuel) are actually pretty fantastic. Its emphasis on the overtime work that allows the men to earn enough money to send back home, and of the frictions between the union rep and the captain of the ship are beautifully rendered. And for its time, its attitude towards the African-American sailors aboard the ship are relatively enlightened (and only relatively).

The vessel moved steadily through the Mediterranean, and out on deck the men worked and chipped rust and mended ladders and performed the routine workaday jobs that comprised their endlessly recurrent chores. Working from the bow aft, the men began painting the vessel. By the time they had finished with the stern, rust would be creeping back again on the bow, the pain would be fading, blistering or peeling, and the timeless monotonous round would begin anew. The pumpmen worked at renewing joints and freeing winches and reach-rods. The wipers painted below, in the ever-increasing heat of the engine room, straddling boilers and generators and turbines, each man performing his allotted function. The oilers made their rounds, the firemen tended their gauges. The twenty-four-hour round-the-clock poker game spun its everlasting way through time. Men disappeared from the card table to eat, stand their watches, turn to at special jobs, or to sleep, and their places were taken by other men who had finished eating, had stood their watches, completed their special jobs, had slept through or were willing to forego sleep to spend their time shuffling bits of cardboard while their hands rifled nervously through the money they kept stacked in front of them. (p. 33).

My interest in the book came from the fact that it happens on an oil tanker and that it specifically has (terrible, racist) passages about Kuwait. Its account of passing through Suez is also interesting (if cringe-worthy for its descriptions of wily natives). Tankers are particularly dangerous to sail. They carry the fuel that can catastrophically destroy them if they are rammed and they become cauldrons of flame and fire and fumes. After recounting one such disaster, the character -who was the only survival of such an accident: “He never forgot that if the general alarm bells had been in working order everyone might have been saved. But there had been no fire or boat drill for over three weeks, though such a drill had been entered in the ship’s log every seventh day as the law required. No one had been aware that the general alarm system was defective. No one had known until it was too late” (p. 70).

And here is the predictably orientalist description of the tanker arriving in Kuwait:

The ship passed through the narrows between the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf, then moved steadily up to Kuwait. They made landfall in the early hours of the morning, with the first rays of the sun striking the sands of the desert and the aluminium paint of the tank farms. A T-shaped dock ran into the sea, an enormous structure, newly created, modern to the last detail, the latest transformation to take place in a land that had known no change for two thousand years. (p. 93)

Once they arrive, they are engulfed in a sandstorm that lacerates the air and makes the docks opaque, covers every surface in the ship, even those behind secured doors, and “[m]onths later, when some piece of engine-room machinery broke down, opening the casings would reveal that the cause of the trouble was the sand which had sifted in during the storm in Kuwait” (p. 95). Once the storm clears, the sailors note that

[t]here were twelve ships at anchor awaiting berth. Most of them were American-built T-2 tankers, operating under foreign flags. There were no restrictions to their activities; they could carry what they pleased, where they pleased, manned by foreign crews, and no American parent company that owned them could be censured, taxed, or held accountable for their activities. (p. 98)

And here is how the Kuwaitis appear in the story -predictably and like so much of the European and US literature of the time, as faceless étrangers, engaged in the inscrutable activities of alien natives, eternally backward amidst so much modernity:

On the docks, the Arabs bowed and knelt on their prayer rugs, their voices raised in praise to their God, their calls rising from between the narrow double lane of ships, from beside the heavy pipelines, from among the cranes and winches, the No Smoking signs displayed everywhere. The fierce sound of their cries was heavy in the night air, piercing the walls of the night like the yelp of a prisoner through the walls of a dungeon. The sailors mocked them, and they looked back in burning anger, out of desert eyes that glittered brown and black with hate, but they neither halted their devotions nor gave sign of their rage by any other mark than the changing shadow of their eyes….

About an hour before midnight the vessel was loaded. But the drinking session before the bos’n’s room did not come to a halt then. There was still plenty of time. The Arabs still had to disconnect the hoses. People from ashore came aboard to make up the cargo papers. The pilot still had to put in his appearance. And from the cracking plant in the distance the bright orange flame from the waste chimney licked against the desert sky. Then thousand lights winked from the stagings of the cracking plant and distillery. The tank farm lay in a solid mass, row upon row of oil tanks, far as the eye could see. (p. 100).

Of the ports to which the ship travels, they prefer the East Asian ones – for all the terrible cliched reasons one comes to expect: the available beautiful feminine petite Asian women (the characterisations are not mine), the ease of access to liquor, the fact that Japan is still really under US military and naval control and the US military police are in charge of all the policing in the Japanese ports where the ship arrives. In the end, this strange little paperback with its melancholy loneliness, alcoholic rage and stupor, and clear class frictions aboard is a document of its time. And all the more readable for conveying this sense of its own historicity.

Robin Moore’s terrible novel, tagged as a “tense novel set in the oil and blood-soaked Middle East” on its cover is a different story. Its writing is so positively atrocious that it does not bear quoting from. The book is both antisemitic and anti-Arab: the claim that the Jews control all US media is made again and again. All the young Arab male characters in it have a proclivity for buggery and rape. The elite Arab men who are admired -Shaykh Zayed of Abu Dhabi, Shaykh Rashid of Dubai, and their “advisors”- are either exulted for their timeless Bedouin masculinity or for their mercantile shrewdness. The main character of the book is an utterly implausible retired US Army lieutenant colonel in love with a half-Iranian half-American hot babe who works in the US Embassy in Tehran. A former US hostage in Iran has claimed that Col Fitz Lodd is based on him. Tehran is meanwhile “the capital of intrigue” in the Middle East, and apparently the most desirable ambassadorial destination in the 1970s. The book is so profoundly terrible, so absolutely horrendous, so awfully plotted, wooden, unsympathetic and offensive you won’t believe. And yet, and yet. This utter and absolute piece of shite is a banned book in Dubai, and where there is smoke, there is fire.

Like Mirvish who used his experience as a merchant seaman to describe the work aboard the tanker of Eternal Voyages, Robin Moore’s connections to various US and local elite in Iran, the UAE and elsewhere, as well as his extensive ties to the Green Berets (he wrote an eponymous novel hat was made into a film and wrote a hit by the same name as well), enrich the political vignettes that are set amidst the macho carnage and terrible storytelling of the book. There are three vignettes of interest here: gold-smuggling; the Iranian occupation of Abu Musa island and the ensuing deal over developing offshore oil fields there; and the rebellion in Dhofar.

The details of gold smuggling operations (or “re-export” as the various operatives insist on calling it) are the most interesting by miles, perhaps because Dubai has continued to be an entrepôt economy dependent on legal or illegal “re-export” of goods to a broad range of recipient countries. As the story goes in Dubai the novel, millions of dollars worth of ten-tola bricks of gold are stored in a high-speed dhow that has been equipped with twenty-millimetre cannons (themselves smuggled away from a shipment of arms sold by the US via the Shah too the Kurds fighting Iraq. Yes, the dizzying deals with local proxies and allies*** -if not necessarily the actual story of the arms-smuggling here- is actually accurate). The dhows travel through international waters blowing away possible Indian Coast Guard intervention, and arrive in the coves of Bombai where the gold, bought from London markets, are sold at ten times the price in India, where the sale of oil was controlled and rationed. As Neha Vora recounts in her article on Indian businessmen in Dubai, Moore’s description of gold-smuggling is rumoured to be based on real events and real characters, although “Mr. Zaveri would neither confirm nor deny this connection.” The details that are of great interest here are of course the full involvement of Shaykh Rashid, who by supporting the venture gets a 20 percent share of the deal. A contemporaneous account of “the end of Raj” in the Gulf describes Dubai as “the biggest of the seven Trucial Shaikhdoms, with about 70,000 people, whose flourishing entrepôt and gold smuggling trade as well as a small new offshore oil field make it the commercial center of the Trucial Coast.” And of course smuggling was at the time the most important form of trade between Arabia and India (at least by dhow), as a fascinating account of dhow trade written in 1982 argues:

During the past ten years, India’s single most valuable illicit export has been silver, a lot of which has vanished from the former Portuguese colony of Daman. In the Gulf states where the silver is sold, Indian dhow captains purchase gold and consumer items, in particular radios, cassettes and wrist watches. These are brought back to the west coast of India and smuggled into towns and cities. The Gujaratis are especially important in this illegal trade and in towns such as Mandvi it is common know- ledge that some of the most successful merchants are dealing with illicit cargo imported on dhows from the Gulf states.

The second story is about the geopolitics of the Iranian occupation of Abu Musa. Moore’s story has the British trading Abu Musa (and the Tunbs) to the Shah for Bahrain. The deal was made with the agreement of the Amir of Sharjah (and tacit approval of Shaykh Rashid) and with the opposition of the Amir of the fictional emirate of Kajmira (presumably Ras Al-Khayma). As a 1975 article by MERIP recounts:

This decade began with Bahrain acquiring full “independence” in August 1971, after an elaborate charade of confrontation in which the Shah of Iran renounced his claim on Bahrain in a way that paved the road for the seizure of Abu Musa and Tunb islands and helped to bolster the rather weak nationalist credentials of the al-Khalifas. British military withdrawal was followed by an agreement with the US to provide a naval station in a ten acre compound containing facilities that accommodate two destroyers, two aircraft, and a “command vessel” equipped with electronic intelligence and communications equipment for monitoring military and commercial shipping movements. This agreement was revoked at the time of the October War in 1973, but just before the withdrawal was to occur in October 1974, Bahrain agreed to a continued US military presence in return for a 600% increase in rent.

The Memorandum of Understanding between Iran and Sharja vis-a-vis Abu Musa was an interesting instance of shared sovereignty where

“neither Iran nor Sharjah will give up its claim to Abu Musa nor recognize the other’s claim,” provided or Iranian” full jurisdiction” in given areas of Abu Musa and “full jurisdiction” for Sharjah in others. It also provided for a “joint sharing” of revenues arising from the exploitation of Abu Musa’s resources. The Memorandum provided for a single company, the Butts Gas and Oil Company, to exploit the oil resources, with the revenues arising there from to be divided equally between the two states [the full text can be read here].

Meanwhile, a 1972 article from India’s Economic and Political Weekly summarises the reactions:

The Arab reaction was mild except for Iraq who instantly severed diplomatic relations both with Iran and Britain. The Parliament of Kuwait passed a resolution denouncing the occupation, the UAR media played it down and Saudi Arabia remained ambiguous.

And another of MERIP’s fab 1975 articles quotes a hilarious report from the Institute for Strategic Studies as saying about Saudi’s posture towards the event:

Saudi Arabia’s armed forces are not well placed to assert the country’s authority outside her borders [hah!]. The army is stationed mainly in the west and in Jordan; the airforce, based mainly in Dharan,..lacks experience; the National Guard, though mobile and ubiquitous, is primarily an internal security force and too lightly armed for offensive operations of any size. Saudi Arabia’s principal asset is less its military power than

King Faisal’s immense personal prestige…. His dignified restraint [hah! hah!] over the Iranian occupation of the islands [the Tunbs and Abu Musa in November 1971] contributed greatly to the defusing of a dangerous situation.

IT’S ALL CONNECTED! In the crappy Moore book, the British/Sharja deal over Abu Musa also gives the Shah the carte blanche to explore for oil beyond the 3-mile marine territorial limit of the island. I haven’t been able to dig up a great deal specifically that deals with this, but I am sure the 1970s deal with the oil company that went exploring in the maritime territories of Abu Musa is somewhere in some business magazine (like MEED or MEES).

Finally, I am going to leave the discussion of the Dhofar. It is such a crappy discussion and the only things it offers is that the British were quite happy for the Dhofari rebellion to bolster their claim to presence in the region, and that the CIA was involved in black ops intercepting arms intended for the rebels. But to find out more about Dhofar, you have to read Abed Takriti’s Monsoon Revolution.

If Mirvish’s book is full of telling detail, Moore’s is full of predictable clichés and bad sex scenes. The only thing about the book that feels somewhat real and palpable is the neverending description of the heat of the summer in Dubai. At a time where few places seem to have had air conditioning (or electricity for that matter), the feel of the all-encompassing hundred percent humidity wetness of 45 degrees Celsius temperatures there feels real. And a sense of the CIA’s involvement in the region. But we already know that.

*** From this fascinating article by Nader Entessar, this tidbit that I did not know: ” In Spring 1974, a US Army operations headquarters was established in the Iranian city of Rezayieh (now Urumiyeh), near the Iraqi border, to advise the Kurdishpeshmergas. Furthermore, a CIA station was reportedly established in the border village of Haj Umran, not far from Barzani’s headquarters.”

UPDATE: Neha Vora’s doctoral thesis has a lot more stuff on the gold trade. She writes:

According to my informants, Dubai is a historical account about how India relied heavily on gold supplied by the Gulf. According to the novel, gold demands were constantly rising, weddings in India and Pakistan were postponed until new gold- shipments could arrive, and rich Indians were desperate to convert their American dollars and sterling into gold. Gold, which cost $35 an ounce in Dubai, could be sold for $105 in India, or traded for silver, usually at a 200% profit. Throughout the book, the characters flirt between the legality and illegality of their actions, which are out in the open in front of certain authorities and institutions, such as Sheikh Rashid and the Dubai Police, but have to be handled diplomatically with Indian officials and the press.