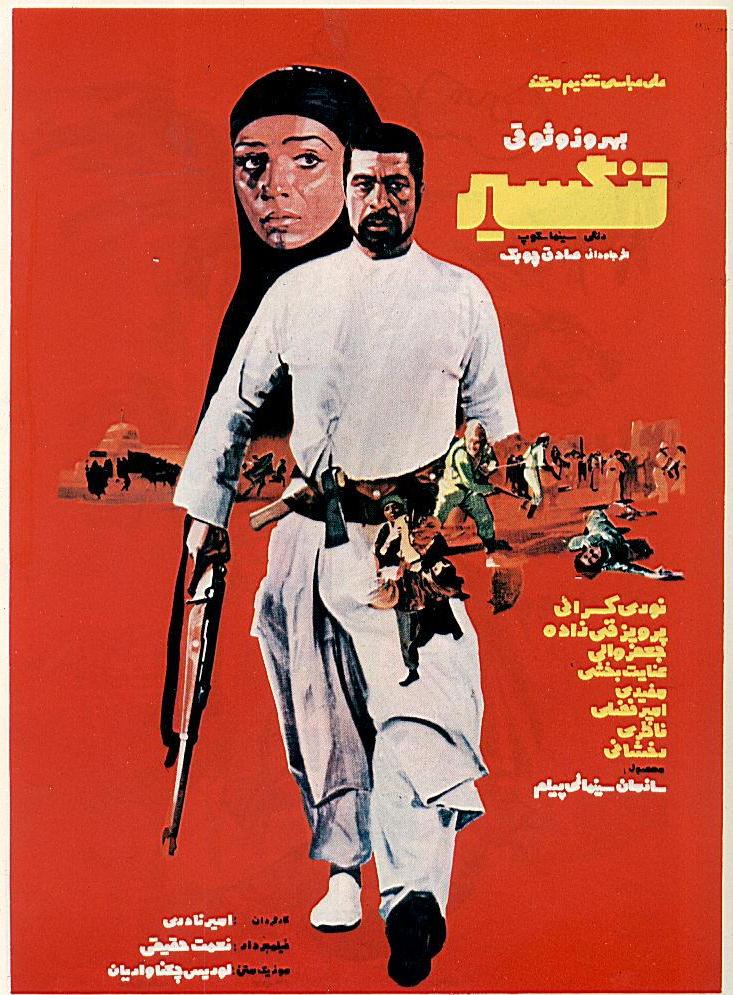

Tangsir

I grew up with a number of Persian-language classic novels on the bookshelves of our house. Throughout my childhood (I was a precocious reader) and teenage years, I tended towards Sadeq Hedayat and Simin Daneshvar and Jalal Al-e-Ahmad. A bit predictable really. My father was from the south; Jahrom, specifically. He had a soft spot for a number of novels and non-fiction books written about the south, and sometimes in the vernacular(s) of the region. Somehow I was never interested.

But age does wonderful things to one’s reading habits and tastes (cf. Moby Dick).

I decided this year, when visiting my mother, to re-read Sadeq Chubak‘s Tangsir (1963) which sits on her bookshelves now -the same hardbound 2nd edition I knew in my childhood, published Tehran in Esfand 1346 (or roughly February 1968) with its price (220 Riyals) embossed on the back cover. It was a moving experience reading it. Two sentences were underlined in the book; one to the effect that one’s integrity mattered more than anything else in the world, including one’s family; and the second that living for 40 years with honour was more worthwhile than living 100 without it. Given the particular political and biographical trajectories of my father, his having underlined those particular sentences was poignant.

But what really struck me about the story was not simply the “heroic anger” of Zar-Muhammad, the hero of the book. It was the intensity of the feel of the places Chubak wrote about. And the vividness of the story’s setting. And the way it was historically situated. The opening of the novel in particular is stunning: its description of the infernal humidity of the coast in summer, the relentlessness of sunshine, makes the reader feel sweaty and thirsty. Its description of sacred trees -under one of which the hero of the book, Mohammad, shelters from the sun- is lovely and affecting in its portrayal of heterodoxy (when we live in such orthodox times). The book’s wonderful glossary itself is extraordinarily readable. And its matter-of-fact portrayal of plurality of publics in Iran: an important character turns out to be an Armenian shop-keeper who supplies the English and others with alcohol.

But even more, it is the geography of Bushehr -and of the sea- the book celebrates. Chubak maps Bushehr through the city’s various neighbourhoods and their relationship to politics, economic production, and the sea. And the British.

The British established a residency in Bushehr in 1763. The city served as a transit point on the trade route from India and a base of trade with the Persian empire. The British then went on to occupy Bushehr outright after they defeated the Iranians in the 1856-1857 Anglo-Persian War, and stayed there for the next 20 years (the residency shifted to Bahrain in 1947).

In the meantime, a large number of English words have become part of Persian (in the south “tomato” is called “tamateh”), and the British with their Indian Army soldiers became quotidian fixtures in Iranian lives and imaginations throughout the southern parts of Iran (Simin Daneshvar’s fabulous Savushun has indelible images of the British and Indian soldiers in Shiraz) – their politics and politicians were already long affixed in the halls of power and in the political machinations of the Iranians.

What Tangsir does is to imagine Bushehr sometime in the late 1920s. The central story is not really related to the British, although they loom large in the background of the story. But what was amazing -like many many other things- was the awareness of how inadequate and incomplete my education in Iranian history has been. A historical figure invoked by Mohammad is Rais Ali Delvari who apparently fought against the British and “died in Mohammad’s arms.”

Ali Delvari (1882-1915) was born in Tangestan, and while in his twenties he took up arms against the occupying British and ended up being killed in the fight (Check out this mesmerising little video by a storyteller who tells the story of Delvari). The details that come out in Chubak’s story are brilliant: Martin guns, the provisioning of weapons, the incorporation of weapons and their names into Farsi and the Persianisation of their names. Interestingly, British histories would want to draw our attention to the Germans doing the provisioning (specifically one Wilhelm Wassmuss who seems to have been a pretty colourful character, so colourful that Christopher Sykes wrote a biography of him, like he did of Orde Wingate).

There is something fascinating in all of this: those most insistently resisting the British -at least in the South- seem to have been “tribes”: Qashqayis, Laristanis, Tangestanis. And of course one of the first thing that Reza Pahlavi does when he comes to power is to bring the tribes to heel; to disarm and disperse and sedentarise them. Chubak records the moment, the caesura, between the popular uprisings against the British and the moment in which these popular groups are subsumed into and subordinated by the state. And the people he portrays embody a history so often left out of the textbooks.

And finally, the sea. The sea is -unlike the British- not in the background. Its corporeality – sense and smell and look, its calm and physicality- are there from the very first scene until the very last. Mohammad was once a helmsman on the Iranian Navy’s sole gunboat, Persepolis (ignore the linked URL’s contemptuous tone if you can. It is very obviously written by an Englishman). The scene in which Mohammad fights a swordfish is extraordinary and beautiful and terrifying all at once. And the sea acts as the possible escape route and the originary point for emigration to Kuwait or Bahrain (incidentally, in the story, Dubai is a backwater; Sharjah is a place where politics and commerce happens; and Kuwait and Bahrain are considered cities on par with Bushehr). The sea is there in the cuts and callouses of Mohammad’s hands and feet. The haze of its salty humid air cushions the palm groves. Its fish are dried, fried, grilled and cooked with rice and bread and dates. What Chubak does brilliantly -beside the invocation of histories excluded from the national canon- is to give a sense of the place which is also so often, literally and figuratively, on the margins of Iranian national imaginary.