Hitching a lift on a US aircraft carrier

The Super Hornet bombers that dropped 8 500-pound JDAM bombs on Islamic State forces in Iraq had flown from the aircraft carrier USS George H W Bush, afloat in the Persian Gulf. It is one among at least 5 Navy ships and 3 ships belonging to the US Marines in the Gulf right now.

The news struck me because I had just finished Geoff Dyer’s Another Great Day at Sea, his account of a writer’s residency aboard the same ship. Rose George and Horatio Clare inter alia have recently written about their adventures aboard freighters (though George also embedded in a EU-NAVFOR ship policing the waters off Somalia). There is a kind of not-so-subtle upmanship in Dyer’s two-week stint aboard a United States Navy aircraft carrier somewhere in the Persian/Arabian Gulf. He specifically avoids a Royal Navy ship, because he fears “the accents, the audible symptoms of the top-to-bottom, toff-to-prole hierarchy that is so clearly manifest in the British military.” There is such a HUGE amount of love for the US and its citizens (especially the martial ones) in this book it sometimes feels uncomfortable.

This definitely is a love song to the American military and it reminds me of the way another of Dyer’s compatriots also feels this pure unadulterated love for Americans in uniform. At the height of the US war in Iraq, British counterinsurgency humanitarian, Emma Sky, a civilian advisor to General Odierno in Iraq was quoted by Tom Ricks as saying “the military is better than the country it protects. “That’s the way I feel about it – America doesn’t deserve its military.”” Dyer must feel the same; his Americans can do no wrong. They are better-mannered, more attractive, more egalitarian, friendlier, more ambitious; they even walk more attractively. He says somewhere something about the loose-limbed confident way Americans walk (and which he attributes to the performative of African-American men’s walk having been absorbed into the general culture). As I was reading that particular section incredulously, I thought of Chimamnda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, in which the African immigrant woman in the US actually reflects in an amused if affectionate sort of way on the strangeness of the American walk.

Maybe it is the unapologetic love for the US and for the sailors he encounters here that makes Dyer’s book remarkably devoid of a political context or a critical examination. Dyer flies to the aircraft carrier from Bahrain and at some points in the story, the ship is only 30 miles from the Iranian coastline, and there are fighter jets flying reconnaissance flights to Iraq or points further afield, and yet we get no sense that the warship is in the Persian Gulf. Maybe he is trying to authentically convey the feel of being aboard what is essentially a floating small-town America, but I think it goes beyond that. There is also no politics in the book. He mentions the killing work of the US Navy only in passing and when the Iranians are mentioned he is flippantly making a wish for Ahmadinejad to magically appear on board so some woman sailor can kick his ass. This utter and complete absence of politics is all the more galling given that Dyer is aboard a ship in a part of the world in which the US has wreaked such death, destruction and violence that we still feel the seismic effects of it so many years later.

Essentially, this is a book about Geoff Dyer, and if you are a Geoff Dyer fan (as there seem to be legions out there) then you will enjoy the painful self-deprecation and the forced humour. But other than the fiery evangelical faith of his shipboard interlocutors nothing ruffles Dyer; he is an atheist and except for a fervent profession of faith, he finds nothing worthy of criticism. The ship portrayed in Dyer’s book is a kind of utopia in which there is no racism, no sexism (he does dutifully footnote sexist incidents in the Navy), and other than differential access to good food, no inequality.

Some of the passages in the book are of some interest: how crowded the carrier is (p. 21); how much food it carries to feed the crew (pp. 26-30); the processes of landing and takeoff that seem a terrifying test of technical knowhow and minutely planned organisation; the proliferation of acronyms (p. 22); and… that’s it really. There are a lot of personal vignettes about the characters onboard, but if you want to learn about what it means to be on a warship, the 3/4 of a chapter by Rose George in her Deep Sea and Foreign Going contains far more technical and political information and opinion than the whole of Dyer’s 188 pages.

Don’t bother reading it if what you want is more than human interest stories about the members of the US military. Certainly not if you want to know about the Persian Gulf. In Dyer’s book, USS George H W Bush might as well be sailing on Mars.

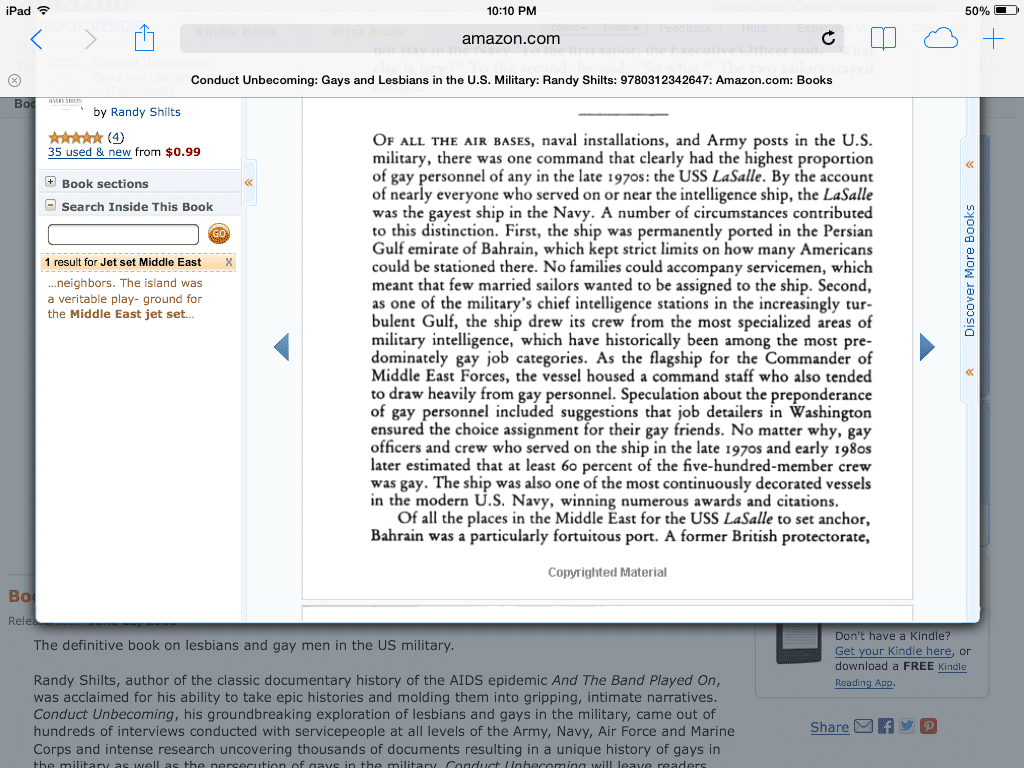

Update: I forgot to add that the book also says very little of homosexuality onboard. Meanwhile, my friend Waleed sent me this screenshot about another ship in the Persian Gulf: